On the eve of the American Civil War in 1861, Scarlett O'Hara lives at Tara, her family's cotton plantation in Georgia, with her parents and two sisters. Scarlett is discovers that her secret love Ashley Wilkes is to be married to his cousin, Melanie Hamilton, and the engagement is to be announced the next day at Ashley's home, the nearby plantation Twelve Oaks. At the Twelve Oaks party, Scarlett is admired by Rhett Butler, who upsets the male guests when he states that the South has no chance of winning the war against the far superior North. Scarlett confesses her love for Ashley, who rebuffs her. Rhett then reveals to a fuming Scarlett that he overheard the conversation but promises to keep her secret.

In retaliation, Scarlett accepts a marriage proposal from Melanie's brother Charles, and they are married before he leaves to fight.

Scarlett is quickly widowed and returns home to Atlanta on the pretext of her grief, but as guessed by the outspoken housemaid, she has only come back to await the return of Ashley. Scarlett, who should not attend parties in deep mourning, attends a charity bazaar with Melanie, thus shocking the societal ladies. Rhett, now a blockade runner for the Confederacy, offers an inordinately large bid to the war effort fund in exchange for a dance with Scarlett, who tells him that he will not win her heart.

The tide of war turns against the Confederacy after the Battle of Gettysburg in which many of the men of Scarlett's town are killed. Scarlett makes another unsuccessful appeal to Ashley while he is visiting on Christmas furlough, although they do share a private kiss in the parlor just before he returns to war.

Eight months later, as the city is besieged by the Union Army in the Atlanta Campaign, Melanie goes into premature labor. Keeping her promise to Ashley to take care of Melanie, Scarlett and her young house servant Prissy must deliver the child without medical assistance. Scarlett calls upon Rhett to bring her home to Tara immediately with Melanie, Prissy, and the baby. He appears with a horse and wagon and takes them out of the city through the burning depot and warehouse district. Instead of accompanying her all the way to Tara, he sends her on her way with a nearly dead horse, helplessly frail Melanie, her baby, and tearful Prissy, and with a passionate kiss as he goes off to fight. On her journey home, Scarlett finds Twelve Oaks burned, ruined and deserted. She is relieved to find Tara still standing but deserted by all except her parents, her sisters, and two servants. Scarlett learns that her mother has just died of typhoid fever and her father's mind has begun to fail under the strain. With Tara pillaged by Union troops and the fields untended, Scarlett vows she will do anything for the survival of her family and herself.

Scarlett sets her family and servants to picking the cotton fields, facing many hardships along the way, including the killing of a Union deserter who attempts to rape her during a burglary. With the defeat of the Confederacy and war's end, Ashley returns, but finds he is of little help at Tara. When Scarlett begs him to run away with her, he confesses his desire for her and kisses her passionately, but says he cannot leave Melanie. Meanwhile, Scarlett's father dies after he is thrown from his horse.

Scarlett realizes she cannot pay the rising taxes on Tara implemented by Reconstructionists, so pays a visit to Rhett in Atlanta. However, upon her visit, Rhett, now in jail, tells her his foreign bank accounts have been blocked, and that her attempt to get his money has been in vain. As Scarlett departs, she encounters her sister's fiancé, the middle-aged Frank Kennedy, who now owns a successful general store and lumber mill. Scarlett lies to Kennedy that her sister married another beau, and after they marry, Scarlett takes over his business and becomes wealthy. When Ashley is offered a job with a bank in the north, Scarlett uses emotional blackmail to persuade him to take over managing the mill.

Frank, Ashley, Rhett and several other accomplices make a night raid on a shanty town after Scarlett narrowly escapes an attempted gang rape while driving through it alone, resulting in Frank's death. With Frank's funeral barely over, Rhett visits Scarlett and proposes marriage, and she accepts. They have a daughter whom Rhett names Bonnie Blue, but Scarlett, still pining for Ashley and chagrined at the perceived ruin of her figure, lets Rhett know that she wants no more children and that they will no longer share a bed.

When visiting the mill one day, Scarlett and Ashley are spied in an embrace by two gossips, including Ashley's sister, India. They eagerly spread the rumor, and Scarlett's reputation is again sullied. Later that evening, Rhett, having heard the rumors, forces Scarlett to attend a birthday party for Ashley. Incapable of believing anything bad of her beloved sister-in-law, Melanie stands by Scarlett's side so that all know that she believes the gossip to be false. After returning home from the party, Scarlett finds Rhett downstairs drunk, and they argue about Ashley. Seething with jealousy, Rhett grabs Scarlett's head and threatens to smash in her skull. When she taunts him that he has no honor, Rhett retaliates by forcing himself onto her, she attempts to physically resist him, but he overpowers her and carries the struggling Scarlett to the bedroom. The next day, Rhett apologizes for his behavior and offers Scarlett a divorce, which she rejects, saying it would be a disgrace, but it is clear that her refusal is due to her sudden reciprocation of his love.

After Rhett returns from an extended trip with Bonnie, Scarlett's attempts at reconciliation are ignored. She informs him that she is pregnant, but an argument ensues which results in her suffering a miscarriage. As Scarlett is recovering, tragedy strikes when Bonnie dies while attempting to jump a fence with her pony. Melanie visits their home to comfort them, but then collapses during a second pregnancy she was warned could kill her.

On her deathbed, Melanie asks Scarlett to look after Ashley for her and to be kind to Rhett. As Scarlett consoles Ashley, Rhett quickly leaves and returns home. Realizing that Ashley only ever truly loved Melanie, Scarlett dashes after Rhett to find him preparing to leave for good. She pleads with him, telling him she realizes now that she had loved him all along, and that she never really loved Ashley. However, he refuses, saying that with Bonnie's death went any chance of reconciliation. As Rhett is about to walk out the door, Scarlett begs him to stay but to no avail, and he walks away into the early morning fog leaving Scarlett weeping on the staircase and vowing to one day win back his love.

Gone With the Wind is a gigantic, sprawling epic of superlative visual merit and entertainment value, with Clark Gable's roguish, cynical and wily Rhett and Vivien Leigh's vain, self-centered and ultimately hardened Scarlett as the most beloved, enduring and complex fictional love-hate lovers to come out of classical Hollywood. It is endlessly rewatchable and impossible not to fall in love with, largely due to its grand scale, the rich, arterial force of its storytelling and magnificent performances. Gone With the Wind is a purely cinematic experience that is truly unforgettable, brimming with color, spectacle and passion, it is a bombastic melodrama acted, staged and designed to perfection that, to this day, remains the benchmark for all epics.

All reviews -

Movies (15)

Gone with the Wind review

Posted : 11 years, 2 months ago on 2 April 2014 04:57

(A review of Gone with the Wind)

Posted : 11 years, 2 months ago on 2 April 2014 04:57

(A review of Gone with the Wind) 0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Seven review

Posted : 11 years, 3 months ago on 29 March 2014 06:40

(A review of Seven)

Posted : 11 years, 3 months ago on 29 March 2014 06:40

(A review of Seven)The newly transferred David Mills and the soon-to-retire William Somerset are homicide detectives who become deeply involved in the case of a sadistic serial killer whose meticulously planned murders correspond to the seven deadly sins: gluttony, greed, sloth, wrath, pride, lust and envy.

In a large unidentified city of near-constant rain, high levels of crime and urban decay, the two detectives are established in their wobbly partnership with starkly contrasting attitudes, personalities and lifestyles: in the opening scene, Somerset's diligent, controlled and alone as we follow his precise morning routine, opposing the relaxed Mills, who wakes up late next to his wife before dressing carelessly on his way to work. Somerset - the mature, cerebral cop - and Mills - headstrong, impulsive - are reluctantly partnered together, but they soon find common ground due to the gentle interference of David's wife Tracy. Weary, exhausted and pained Somerset is just one week away from a well-deserved retirement and fiery, idealistic hotshot Mills is touted as his cock-sure replacement; their next case will span the following seven days and change their lives forever. On Monday, the detectives discover an obese man who was forced to feed himself to death, representing "Gluttony." The next day, they discover a fatal bloodletting of a rich attorney, representing "Greed". The detectives find a set of fingerprints, as well as additional clues at both murder scenes, and believe they're chasing a serial killer relating to the seven deadly sins. Two days later, the fingerprints leads them to an apartment where they find an emaciated man strapped to a bed. Though he initially appears to be dead, it soon is discovered that the man has been kept alive and entirely immobile by the killer for exactly one year to the day; a drug dealer and child molester before his captivity, this victim represents "Sloth". Though unable to learn anything from the insensate victim, the detectives agree that the killer has planned these crimes for more than a year.

Tracy Mills is unhappy with their recent move to the city. She meets Somerset after the first two murders and he becomes Tracy's confidante. Upon learning that she is pregnant but has not told her husband, Somerset confides in her his fear that such an immoral, ravaged city is no place to start a family, and reveals that he had ended a relationship years earlier after pressuring his girlfriend to have an abortion. Somerset, knowing that David would more than likely want to keep the baby, advises her not to tell him if she plans to have an abortion.

Using library records, Somerset and Mills track down a man named John Doe, who has frequently checked out books related to the deadly sins. When Doe finds the detectives approaching his apartment, he opens fire on them and flees, chased by Mills. Eventually, Doe gains the upper hand and holds Mills at gunpoint, but then abruptly leaves, sparing Mills's life. Investigation of Doe's apartment finds handwritten volumes of his irrational judgments and clues leading to another potential victim, but no fingerprints. They arrive too late to find their "Lust" victim, a prostitute killed by an unwilling man wearing a bladed S&M device, forced by Doe to simultaneously rape and kill her, severely traumatizing the man. On Sunday morning, they investigate the death of a young model whose face had been mutilated. Having chosen to kill herself rather than live with a disfigured face, she is the victim of "Pride". As they return to the police station, Doe goes to the police station and offers himself for arrest, with the blood of the model and an unidentified victim on his hands. They find out that he has been cutting the skin off his fingers to avoid leaving fingerprints. Through his lawyer, Doe claims he will lead the two detectives to the last two bodies and confess to the crimes, or otherwise will plead insanity. Though Somerset is worried, Mills agrees to the demand. Doe directs the two detectives to a remote desert area far from the city; along the way, he claims that God told him to punish the wicked and reveal the world for the awful place that it is. He also makes cryptic comments toward Mills. After arriving at the location, a delivery van approaches; Somerset intercepts the driver, leaving Mills and Doe alone. The driver hands over a package he was instructed to deliver at precisely this time and location, which is 7 p.m. While Mills holds Doe at gunpoint, Doe mentions how much he admires him, but does not say why. Somerset opens the package and recoils in horror at the sight of the contents. He races back to warn Mills not to listen to Doe, but the killer reveals that the box contains Tracy's head. Doe claims to represent the sin of "Envy"; he was envious of Mills's normal life, and killed Tracy after failing to "play husband" with her. He then taunts the distraught Mills with the knowledge that Tracy was pregnant, asking Mills to kill him and become "Wrath". Somerset pleads with Mills not to let Doe win, but he cannot contain Mills, who then repeatedly shoots Doe, killing him, therefore completing his "work".

It is a nihilistic, bleak and somewhat depressive ending, but as such encapsulates and reiterates the entire thematic point of the film, that the world is a dark, hellish place that inhabits good and evil: those of whom commit horrendous crimes, and the people who try to stop them. In particular, Se7en is a serious artistic meditation on the ambiguous, murky nature of evil, depicted in the film as inhumanity, sin and crime; its city conjures up chillingly poetic imagery, presenting the destructive effects of crime with dirty, polluted and oppressively rain-soaked claustrophobia. Visually and stylistically, it is a grim, dark, dismal world, a look achieved through the chemical process of bleach bypassing, wherein the silver in the film stock was not removed, which in turn deepened the dark, shadowy images in the film and increased its overall tonal quality.

Complex, artistic and disturbing, Se7en is a brutal, grimy shocker that holds your mind captive to its psychologically violent subject matter and unforgettable imagery. It is not a masterpiece on the spectrum of more purely cinematic serial killer genre films such as The Silence of the Lambs, but it is interesting and thrilling enough to be called a work of jagged, uncompromisingly dark genius.

In a large unidentified city of near-constant rain, high levels of crime and urban decay, the two detectives are established in their wobbly partnership with starkly contrasting attitudes, personalities and lifestyles: in the opening scene, Somerset's diligent, controlled and alone as we follow his precise morning routine, opposing the relaxed Mills, who wakes up late next to his wife before dressing carelessly on his way to work. Somerset - the mature, cerebral cop - and Mills - headstrong, impulsive - are reluctantly partnered together, but they soon find common ground due to the gentle interference of David's wife Tracy. Weary, exhausted and pained Somerset is just one week away from a well-deserved retirement and fiery, idealistic hotshot Mills is touted as his cock-sure replacement; their next case will span the following seven days and change their lives forever. On Monday, the detectives discover an obese man who was forced to feed himself to death, representing "Gluttony." The next day, they discover a fatal bloodletting of a rich attorney, representing "Greed". The detectives find a set of fingerprints, as well as additional clues at both murder scenes, and believe they're chasing a serial killer relating to the seven deadly sins. Two days later, the fingerprints leads them to an apartment where they find an emaciated man strapped to a bed. Though he initially appears to be dead, it soon is discovered that the man has been kept alive and entirely immobile by the killer for exactly one year to the day; a drug dealer and child molester before his captivity, this victim represents "Sloth". Though unable to learn anything from the insensate victim, the detectives agree that the killer has planned these crimes for more than a year.

Tracy Mills is unhappy with their recent move to the city. She meets Somerset after the first two murders and he becomes Tracy's confidante. Upon learning that she is pregnant but has not told her husband, Somerset confides in her his fear that such an immoral, ravaged city is no place to start a family, and reveals that he had ended a relationship years earlier after pressuring his girlfriend to have an abortion. Somerset, knowing that David would more than likely want to keep the baby, advises her not to tell him if she plans to have an abortion.

Using library records, Somerset and Mills track down a man named John Doe, who has frequently checked out books related to the deadly sins. When Doe finds the detectives approaching his apartment, he opens fire on them and flees, chased by Mills. Eventually, Doe gains the upper hand and holds Mills at gunpoint, but then abruptly leaves, sparing Mills's life. Investigation of Doe's apartment finds handwritten volumes of his irrational judgments and clues leading to another potential victim, but no fingerprints. They arrive too late to find their "Lust" victim, a prostitute killed by an unwilling man wearing a bladed S&M device, forced by Doe to simultaneously rape and kill her, severely traumatizing the man. On Sunday morning, they investigate the death of a young model whose face had been mutilated. Having chosen to kill herself rather than live with a disfigured face, she is the victim of "Pride". As they return to the police station, Doe goes to the police station and offers himself for arrest, with the blood of the model and an unidentified victim on his hands. They find out that he has been cutting the skin off his fingers to avoid leaving fingerprints. Through his lawyer, Doe claims he will lead the two detectives to the last two bodies and confess to the crimes, or otherwise will plead insanity. Though Somerset is worried, Mills agrees to the demand. Doe directs the two detectives to a remote desert area far from the city; along the way, he claims that God told him to punish the wicked and reveal the world for the awful place that it is. He also makes cryptic comments toward Mills. After arriving at the location, a delivery van approaches; Somerset intercepts the driver, leaving Mills and Doe alone. The driver hands over a package he was instructed to deliver at precisely this time and location, which is 7 p.m. While Mills holds Doe at gunpoint, Doe mentions how much he admires him, but does not say why. Somerset opens the package and recoils in horror at the sight of the contents. He races back to warn Mills not to listen to Doe, but the killer reveals that the box contains Tracy's head. Doe claims to represent the sin of "Envy"; he was envious of Mills's normal life, and killed Tracy after failing to "play husband" with her. He then taunts the distraught Mills with the knowledge that Tracy was pregnant, asking Mills to kill him and become "Wrath". Somerset pleads with Mills not to let Doe win, but he cannot contain Mills, who then repeatedly shoots Doe, killing him, therefore completing his "work".

It is a nihilistic, bleak and somewhat depressive ending, but as such encapsulates and reiterates the entire thematic point of the film, that the world is a dark, hellish place that inhabits good and evil: those of whom commit horrendous crimes, and the people who try to stop them. In particular, Se7en is a serious artistic meditation on the ambiguous, murky nature of evil, depicted in the film as inhumanity, sin and crime; its city conjures up chillingly poetic imagery, presenting the destructive effects of crime with dirty, polluted and oppressively rain-soaked claustrophobia. Visually and stylistically, it is a grim, dark, dismal world, a look achieved through the chemical process of bleach bypassing, wherein the silver in the film stock was not removed, which in turn deepened the dark, shadowy images in the film and increased its overall tonal quality.

Complex, artistic and disturbing, Se7en is a brutal, grimy shocker that holds your mind captive to its psychologically violent subject matter and unforgettable imagery. It is not a masterpiece on the spectrum of more purely cinematic serial killer genre films such as The Silence of the Lambs, but it is interesting and thrilling enough to be called a work of jagged, uncompromisingly dark genius.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

A Clockwork Orange

Posted : 11 years, 3 months ago on 18 March 2014 04:02

(A review of A Clockwork Orange)

Posted : 11 years, 3 months ago on 18 March 2014 04:02

(A review of A Clockwork Orange)Stanley Kubrick’s explicit and darkly ironic examination of delinquency and its socio-cultural consequences, A Clockwork Orange, dissects the nature of violence within a familiar, near-future metropolis, albeit with satirical verve.

It is a dazzling work of raddled genius, an urban excerpt in which the dystopian nightmare is disturbingly submersible; as a viewer, you are completely immersed within its stark backdrop, its offbeat characters and their idiosyncrasies, impelled to watch even if what you are watching is not particularly pleasant. Classical music-loving proto-punk Alex and his "Droogs" spend their nights getting high on spiked milk before embarking on "a little of the old ultraviolence," such as terrorizing a writer, Mr. Alexander, and gang raping his wife (who later dies as a result). After Alex is jailed for bludgeoning the Cat Lady to death with one of her phallic sculptures, he submits to the Ludovico behavior modification technique to earn his freedom; he's conditioned to abhor violence through watching gory movies, and even his adored Beethoven is turned against him. Returned to the world defenseless, Alex becomes the victim of his prior victims, with Mr. Alexander using Beethoven's Ninth to inflict the greatest pain of all. When society sees what the state has done to Alex, however, the politically expedient move is made.

Alex is the narrator and protagonist of the film, but he is also the villain, which somewhat refreshes the logic of narrative cinema, and as the story unfolds, you as a viewer are won over by his manipulative narration and subconsciously complicit in his acts of crime, terror and sadism. Uncomfortable as it is being placed in the perspective of a sociopathic deliquent, his acts of amusement are visually depicted as violence, but from an amoral point of view, and therefore it is not gratuitous or mindless, it is artistic realism. Both the main sexual violence set pieces are almost hypnotic in their stylistic glory, taking place in lavish country homes with pseudo-sexual décor – perhaps to contrast Alex’s own dilapidated council estate flat – filmed with subversive, balletic ritualism and lit like a fashion shoot.

Kubrick's detached view of the state's economy of violence: how criminal abhorrence is countered with clinical, scientific subjection. Alex's violence is horrific, yet it is an aesthetically calculated fact of his existence; his charisma makes the icily clinical Ludovico treatment seem more negatively abusive than positively therapeutic. Alex may be a sadist, but the state's autocratic control is another violent act, rather than a solution.

It examines its subject with real cost, and in true Kubrick fashion, the story closes in on itself at the last moment and becomes cinematic reverie of the highest order with a visually arresting final series of shots suggestively depicting Alex returning to his old ultraviolent self through his non-repellent fantasies. Casting a coldly pessimistic view on the then-future of the late 1970s, Kubrick and production designer John Barry created a world of high-tech cultural decay, mixing old details like bowler hats with bizarrely alienating "new" environments like the Milkbar. Kubrick explores the central questions of Anthony Burgess' novel, but with his trademark subversive, clinical vision. After aversion therapy, Alex behaves like a good member of society, but not by choice. His goodness is involuntary; he has become the titular clockwork orange — organic on the outside, mechanical on the inside. In the prison, after witnessing the Technique in action on Alex, the chaplain criticizes it as false, arguing that true goodness must come from within. This leads to the theme of abusing liberties — personal, governmental, civil — by Alex, with two conflicting political forces, the Government and the Dissidents, both manipulating Alex for their purely political ends. The story critically portrays the "conservative" and "liberal" parties as equal, for using Alex as a means to their political ends: the writer Mr Alexander wants revenge against Alex and sees him as a means of definitively turning the populace against the incumbent government and its new regime.

In its entirety, A Clockwork Orange is a nightmarishly beautiful fable of a heightened, devoid and broken future that is sadly accurate in its prediction, cementing the film as a sort of savagely bleak premonition of today's totalitarian governments, desensitized youth and prominent gang culture. Upon its release, opinion was divided on the meaning of Kubrick's detached view of this shocking future, but, whether the discord drew the curious or Kubrick's scathing diagnosis spoke to the chaotic cultural moment, and it has become one of Kubrick's most culturally significant masterpieces that hits you in the head with the director's assurance and his typical cynicism, paranoia and visual flair; it is an overwhelming, poignantly prophetic exploration of morality, a social satire of state control, crime and punishment, redemption, and a running lecture on free will that is classic cinema at its most cerebral, influential and socially significant. It is truly unmissable.

It is a dazzling work of raddled genius, an urban excerpt in which the dystopian nightmare is disturbingly submersible; as a viewer, you are completely immersed within its stark backdrop, its offbeat characters and their idiosyncrasies, impelled to watch even if what you are watching is not particularly pleasant. Classical music-loving proto-punk Alex and his "Droogs" spend their nights getting high on spiked milk before embarking on "a little of the old ultraviolence," such as terrorizing a writer, Mr. Alexander, and gang raping his wife (who later dies as a result). After Alex is jailed for bludgeoning the Cat Lady to death with one of her phallic sculptures, he submits to the Ludovico behavior modification technique to earn his freedom; he's conditioned to abhor violence through watching gory movies, and even his adored Beethoven is turned against him. Returned to the world defenseless, Alex becomes the victim of his prior victims, with Mr. Alexander using Beethoven's Ninth to inflict the greatest pain of all. When society sees what the state has done to Alex, however, the politically expedient move is made.

Alex is the narrator and protagonist of the film, but he is also the villain, which somewhat refreshes the logic of narrative cinema, and as the story unfolds, you as a viewer are won over by his manipulative narration and subconsciously complicit in his acts of crime, terror and sadism. Uncomfortable as it is being placed in the perspective of a sociopathic deliquent, his acts of amusement are visually depicted as violence, but from an amoral point of view, and therefore it is not gratuitous or mindless, it is artistic realism. Both the main sexual violence set pieces are almost hypnotic in their stylistic glory, taking place in lavish country homes with pseudo-sexual décor – perhaps to contrast Alex’s own dilapidated council estate flat – filmed with subversive, balletic ritualism and lit like a fashion shoot.

Kubrick's detached view of the state's economy of violence: how criminal abhorrence is countered with clinical, scientific subjection. Alex's violence is horrific, yet it is an aesthetically calculated fact of his existence; his charisma makes the icily clinical Ludovico treatment seem more negatively abusive than positively therapeutic. Alex may be a sadist, but the state's autocratic control is another violent act, rather than a solution.

It examines its subject with real cost, and in true Kubrick fashion, the story closes in on itself at the last moment and becomes cinematic reverie of the highest order with a visually arresting final series of shots suggestively depicting Alex returning to his old ultraviolent self through his non-repellent fantasies. Casting a coldly pessimistic view on the then-future of the late 1970s, Kubrick and production designer John Barry created a world of high-tech cultural decay, mixing old details like bowler hats with bizarrely alienating "new" environments like the Milkbar. Kubrick explores the central questions of Anthony Burgess' novel, but with his trademark subversive, clinical vision. After aversion therapy, Alex behaves like a good member of society, but not by choice. His goodness is involuntary; he has become the titular clockwork orange — organic on the outside, mechanical on the inside. In the prison, after witnessing the Technique in action on Alex, the chaplain criticizes it as false, arguing that true goodness must come from within. This leads to the theme of abusing liberties — personal, governmental, civil — by Alex, with two conflicting political forces, the Government and the Dissidents, both manipulating Alex for their purely political ends. The story critically portrays the "conservative" and "liberal" parties as equal, for using Alex as a means to their political ends: the writer Mr Alexander wants revenge against Alex and sees him as a means of definitively turning the populace against the incumbent government and its new regime.

In its entirety, A Clockwork Orange is a nightmarishly beautiful fable of a heightened, devoid and broken future that is sadly accurate in its prediction, cementing the film as a sort of savagely bleak premonition of today's totalitarian governments, desensitized youth and prominent gang culture. Upon its release, opinion was divided on the meaning of Kubrick's detached view of this shocking future, but, whether the discord drew the curious or Kubrick's scathing diagnosis spoke to the chaotic cultural moment, and it has become one of Kubrick's most culturally significant masterpieces that hits you in the head with the director's assurance and his typical cynicism, paranoia and visual flair; it is an overwhelming, poignantly prophetic exploration of morality, a social satire of state control, crime and punishment, redemption, and a running lecture on free will that is classic cinema at its most cerebral, influential and socially significant. It is truly unmissable.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Shame review

Posted : 12 years, 4 months ago on 21 February 2013 02:23

(A review of Shame)

Posted : 12 years, 4 months ago on 21 February 2013 02:23

(A review of Shame)Although Brandon's sex addiction is the catalyst for the narrative, those explicit scenes (of which there are many) are not titillating or erotic, they are absolutely awful to watch because he is not doing it for pleasure, but as an extension of his inability to feel or develop any sort relationship; sex is intimacy to him and it is a daily need. Even though it is slow-paced and melancholic, exploring a taboo subject with frank detail and realism, the film works better as an analysis of emotional detachment, which is challenged by the arrival of Brandon's equally troubled sister Sissy. We are not told of their background, but considering how damaged they both are and their opposing borderline personalities, it is clear that whatever childhood they had, it was not decent or relatively normal. Brandon is repulsed by Sissy's need for affection and intimacy, without which she self-destructs. It is a dark and moving film at times, but fatally cold by its open ending, which proceeds Brandon's breakdown and realisation of his love for Sissy to have meant nothing. It works, definitely, but is far more interesting to look at than it is to explore in a deeper sense with multiple viewings.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Titanic review

Posted : 12 years, 4 months ago on 20 February 2013 03:55

(A review of Titanic)

Posted : 12 years, 4 months ago on 20 February 2013 03:55

(A review of Titanic)Titanic

// James Cameron pitched his idea of 'Romeo & Juliet on the Titanic' to 20th Century Fox, who were unsure of its commercial prospects but wanted a long partnership with him, they greenlit the project with an unprecedented $200m budget. Titanic was released in 1997 to become the highest-grossing film of all-time, earning two billion dollars. 20th Century Fox were very happy indeed to have taken the risk, but I'll bet they were as worried as everyone else that it was going to sink.

As the story goes, Jack (Leonardo DiCaprio) a poor young man who wins himself a ticket home on the maiden voyage of the world's most famous - and soon to be infamous - ocean liner. Rose (Kate Winslet) a rich girl internally dying amid the rigid control and duty of post-Edwardian society, forcibly and miserably engaged to beastly aristocrat Cal Hockley, the saviour to her family's debts. In a fit of sudden terror, she considers throwing herself into the ocean off the back of the ship, but heroic Jack saves her from a (pre-emptive) fate worse than death (cosseted social strictures) as he believes she wouldn't have jumped; his directness, optimism and artistry are to capture Rose's heart, but the only obstacle that tears them apart is the watery grave most of the passengers perish in. Old Rose recounts the events of 1912 with detail, frankness and surprising clarity in comparison to her fading short-term, but as she states, the only place Jack exists is in her memory, and by the end of the film, they are reunited upon her fulfilling his pre-death promise that she will last until old age after a happy, varied life, dying peacefully in her bed, however, not before physically (and metaphysically) returning the heart of the ocean necklace (as well as that of her own to Jack and the Titanic) to its rightful place, thus being reunited with her true love. Essentially, Titanic explores social position, class division and the stoicism and nobility of a bygone era, presenting us with the nature of human survival - its purest form is raw and instinctive during the sinking - the majority of the ship's officers and their critically bad actions and shoddy handling of the disaster. Perhaps the most shocking idea is the folly and laughable disbelief that any ship could ever possibly be unsinkable, and why was nobody educated in the dangers of travelling on ocean liners? Even more so, why weren't tests carried out of the possibilities such as iceberg collision compared with that of the poorly built engineering? Outdated safety features and tests were carried out during its production, and maritime regulations were not up to standard, lacking enough lifeboats to accommodate even half its passengers. Perhaps it could be said that the disaster was very much guaranteed. Titanic teaches the viewer that life is uncertain, the future unknowable and the unthinkable possible; no doubt the passengers were led to their deaths in the misguided belief the ship they were travelling upon was unsinkable, it is infamous for that press label alone and the deaths of 1, 514 people.

For any film fan, it is an undeniable spectacle of epic grandeur, action and romance. Despite its popularity, many people defy its power and refuse to acknowledge its brilliance. However, for three hours of cinematic splendour and pure entertainment, its a masterpiece. Try to derail it and you will come across as those cynical fools who bashed every James Cameron film for its lack of subtlety, but if you don't like it, that's your opinion. After all, who remembers the crowds of people, queues and revellers outside the cinema in 1997? Two-billion dollars worth make this the planet's favourite film, that's a fact.

// James Cameron pitched his idea of 'Romeo & Juliet on the Titanic' to 20th Century Fox, who were unsure of its commercial prospects but wanted a long partnership with him, they greenlit the project with an unprecedented $200m budget. Titanic was released in 1997 to become the highest-grossing film of all-time, earning two billion dollars. 20th Century Fox were very happy indeed to have taken the risk, but I'll bet they were as worried as everyone else that it was going to sink.

As the story goes, Jack (Leonardo DiCaprio) a poor young man who wins himself a ticket home on the maiden voyage of the world's most famous - and soon to be infamous - ocean liner. Rose (Kate Winslet) a rich girl internally dying amid the rigid control and duty of post-Edwardian society, forcibly and miserably engaged to beastly aristocrat Cal Hockley, the saviour to her family's debts. In a fit of sudden terror, she considers throwing herself into the ocean off the back of the ship, but heroic Jack saves her from a (pre-emptive) fate worse than death (cosseted social strictures) as he believes she wouldn't have jumped; his directness, optimism and artistry are to capture Rose's heart, but the only obstacle that tears them apart is the watery grave most of the passengers perish in. Old Rose recounts the events of 1912 with detail, frankness and surprising clarity in comparison to her fading short-term, but as she states, the only place Jack exists is in her memory, and by the end of the film, they are reunited upon her fulfilling his pre-death promise that she will last until old age after a happy, varied life, dying peacefully in her bed, however, not before physically (and metaphysically) returning the heart of the ocean necklace (as well as that of her own to Jack and the Titanic) to its rightful place, thus being reunited with her true love. Essentially, Titanic explores social position, class division and the stoicism and nobility of a bygone era, presenting us with the nature of human survival - its purest form is raw and instinctive during the sinking - the majority of the ship's officers and their critically bad actions and shoddy handling of the disaster. Perhaps the most shocking idea is the folly and laughable disbelief that any ship could ever possibly be unsinkable, and why was nobody educated in the dangers of travelling on ocean liners? Even more so, why weren't tests carried out of the possibilities such as iceberg collision compared with that of the poorly built engineering? Outdated safety features and tests were carried out during its production, and maritime regulations were not up to standard, lacking enough lifeboats to accommodate even half its passengers. Perhaps it could be said that the disaster was very much guaranteed. Titanic teaches the viewer that life is uncertain, the future unknowable and the unthinkable possible; no doubt the passengers were led to their deaths in the misguided belief the ship they were travelling upon was unsinkable, it is infamous for that press label alone and the deaths of 1, 514 people.

For any film fan, it is an undeniable spectacle of epic grandeur, action and romance. Despite its popularity, many people defy its power and refuse to acknowledge its brilliance. However, for three hours of cinematic splendour and pure entertainment, its a masterpiece. Try to derail it and you will come across as those cynical fools who bashed every James Cameron film for its lack of subtlety, but if you don't like it, that's your opinion. After all, who remembers the crowds of people, queues and revellers outside the cinema in 1997? Two-billion dollars worth make this the planet's favourite film, that's a fact.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

The Shining review

Posted : 12 years, 4 months ago on 11 February 2013 03:58

(A review of The Shining)

Posted : 12 years, 4 months ago on 11 February 2013 03:58

(A review of The Shining)The Shining

// Kubrick's magnificently capacious spooker capitalises on A Clockwork Orange's luridly colourful, bizarrely beautiful and often baroque production design; visually it is astounding, but delves further into logistical marvel and psychology than any of his previous works.

Such as the true nature of subtext has puzzled viewers for more than thirty years; Kubrick ditched the novel's formulaic horror elements in favour of an incipient study in the madness and ambiguous evil of Jack Torrence, a struggling novelist. With The Shining, Kubrick, akin to his poetic treatment of the ingenuity and folly of mankind in sci-fi masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey, elevated horror to a different plane, removing its silly campness and bogeymen to infuriate and bedazzle with sinewy suggestion and sumptuous, awe-inspiring technique. Technically and artistically, there is no better film in the genre. Its chills are less direct (that is until Torrance finally throws off the shackles of sanity), perhaps something deeper that creeps under the skin to unsettle and disturb but never for the reasons you think. It is not a film that can be easily forgotten as with most generic or sub-generic horror films, it is quite simply a masterpiece that will never be deciphered.

In accordance with the Kubrick legend, the process of making the movie took meticulousness to staggering levels — Shelley Duvall was reputedly forced to do no less than 127 takes of one scene; Nicholson was force fed endless cheese sandwiches (which he loathes) to generate a sense of inner revulsion, and the recent invention of the Steadicam (by Garret Brown) fuelled Kubrick's obsessive quest for perfection. The result is gloriously precision-made. The use of sound especially (listen to the remarkable rhythm qf silence then clatter set up by Danny pedalling his trike intermittently over carpet then wooden floor.) And that's not forgetting the procession of captivating images: a lift opening to spill gallons of blood in slow motion; a beautiful woman transformed into a rotting old hag in Jack's arms; the coitally-connected tuxedo and savage-faced human/bear staring ominously at Wendy; and, as a million posters now attest, Jack's leering face through the gaping axe wound in the door. Alive with portent and symbolism, every frame of the film brims with Kubrick's genius for implying psychological purpose in setting: the hotel's tight, sinister labyrinth of corridors; its cold, sterile bathrooms; the lavish, illusionary ballroom. This was horror of the mind transposed to place (or, indeed, vice versa). The clarity of the photography and the weird perspectives constantly alluding to Torrance's twisted state of mind. The supernatural elements are more elusive than the depiction of his madness. The "shining" itself — the title comes from the line "We all shine on" in the John Lennon song Instant Karma — is the uncanny ability to see dark visions of the truth (young Danny manifests the power through an imaginary alter-ego Tony). A power separate from yet entwined with the evil that dwells in the building (the whole family will come to experience it). The Overlook, sacrilegiously built on an ancient Indian burial ground (a minor point for Kubrick and stolen by Poltergeist), is haunted by evil spirits. When Jack enters the sprawling ballroom, he is entering into the building's dark heart (possibly even Hell itself): "Your credit's fine Mr Torrance." It's unclear whether it is Torrance's growing insanity that invites this or The Overlook itself taking possession of his soul. Grady, the previous caretaker, a man driven to slaughter his family (the source of Danny's disturbing second sight of the blue-dressed sisters) is another of Torrance's visitation states — "You have always been the caretaker," Grady suggests menacingly. The evil may have always been there in Jack, The Overlook merely awakened it. It's a question the whole film is posing: does the potential for evil reside in all men, just waiting to come to life? The final shot of Torrance trapped inside a photograph of the ballroom in 1921 hints at his destiny: he has become one with The Overlook — as he always was (death, you see, is never the end).

Perhaps the very reason it is held in such high regard lies in the point of Kubrick never explaining its genius - meaning that its focal power cannot be reduced.

// Kubrick's magnificently capacious spooker capitalises on A Clockwork Orange's luridly colourful, bizarrely beautiful and often baroque production design; visually it is astounding, but delves further into logistical marvel and psychology than any of his previous works.

Such as the true nature of subtext has puzzled viewers for more than thirty years; Kubrick ditched the novel's formulaic horror elements in favour of an incipient study in the madness and ambiguous evil of Jack Torrence, a struggling novelist. With The Shining, Kubrick, akin to his poetic treatment of the ingenuity and folly of mankind in sci-fi masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey, elevated horror to a different plane, removing its silly campness and bogeymen to infuriate and bedazzle with sinewy suggestion and sumptuous, awe-inspiring technique. Technically and artistically, there is no better film in the genre. Its chills are less direct (that is until Torrance finally throws off the shackles of sanity), perhaps something deeper that creeps under the skin to unsettle and disturb but never for the reasons you think. It is not a film that can be easily forgotten as with most generic or sub-generic horror films, it is quite simply a masterpiece that will never be deciphered.

In accordance with the Kubrick legend, the process of making the movie took meticulousness to staggering levels — Shelley Duvall was reputedly forced to do no less than 127 takes of one scene; Nicholson was force fed endless cheese sandwiches (which he loathes) to generate a sense of inner revulsion, and the recent invention of the Steadicam (by Garret Brown) fuelled Kubrick's obsessive quest for perfection. The result is gloriously precision-made. The use of sound especially (listen to the remarkable rhythm qf silence then clatter set up by Danny pedalling his trike intermittently over carpet then wooden floor.) And that's not forgetting the procession of captivating images: a lift opening to spill gallons of blood in slow motion; a beautiful woman transformed into a rotting old hag in Jack's arms; the coitally-connected tuxedo and savage-faced human/bear staring ominously at Wendy; and, as a million posters now attest, Jack's leering face through the gaping axe wound in the door. Alive with portent and symbolism, every frame of the film brims with Kubrick's genius for implying psychological purpose in setting: the hotel's tight, sinister labyrinth of corridors; its cold, sterile bathrooms; the lavish, illusionary ballroom. This was horror of the mind transposed to place (or, indeed, vice versa). The clarity of the photography and the weird perspectives constantly alluding to Torrance's twisted state of mind. The supernatural elements are more elusive than the depiction of his madness. The "shining" itself — the title comes from the line "We all shine on" in the John Lennon song Instant Karma — is the uncanny ability to see dark visions of the truth (young Danny manifests the power through an imaginary alter-ego Tony). A power separate from yet entwined with the evil that dwells in the building (the whole family will come to experience it). The Overlook, sacrilegiously built on an ancient Indian burial ground (a minor point for Kubrick and stolen by Poltergeist), is haunted by evil spirits. When Jack enters the sprawling ballroom, he is entering into the building's dark heart (possibly even Hell itself): "Your credit's fine Mr Torrance." It's unclear whether it is Torrance's growing insanity that invites this or The Overlook itself taking possession of his soul. Grady, the previous caretaker, a man driven to slaughter his family (the source of Danny's disturbing second sight of the blue-dressed sisters) is another of Torrance's visitation states — "You have always been the caretaker," Grady suggests menacingly. The evil may have always been there in Jack, The Overlook merely awakened it. It's a question the whole film is posing: does the potential for evil reside in all men, just waiting to come to life? The final shot of Torrance trapped inside a photograph of the ballroom in 1921 hints at his destiny: he has become one with The Overlook — as he always was (death, you see, is never the end).

Perhaps the very reason it is held in such high regard lies in the point of Kubrick never explaining its genius - meaning that its focal power cannot be reduced.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Psycho review

Posted : 12 years, 5 months ago on 24 January 2013 04:57

(A review of Psycho)

Posted : 12 years, 5 months ago on 24 January 2013 04:57

(A review of Psycho)Psycho

// Marion Crane, a platinum-blonde officeworker, is trusted by everyone who knows her as an honest, decent good woman. However, on her lunch breaks she rushes immoral activities with her lover, who is broke due to paying out alimony to an ex-wife. Desperate to marry him, Marion is handed $40,000 from a flirtatious old client. Unable to resist temptation i.e. the urge to solve her problems with her lover, she flees back to her apartment with the money. After some mental backtracking and imaginary scenarios, Marion ignores her desires and drives into the night, waking up to a suspicious policeman, whom follows her as she trades in her car to throw him off the trail. On the highway to Fairvale, Marion stops off at the empty, decrepit Bates motel; so secluded that her presence will not be noticed by the police. Upon her arrival though, she doesn't bet on the proprietor - intense, jumpy and withdrawn young man Norman - and domineering mother to make sure she truly regrets her moment of madness and want to return the money. But it is too late; she is stabbed to death in the shower by a completely shadowed figure strongly resembling invalid mother from the overlooking draconian house. Marion's lover Sam and her sister Lila become suspicious along with Arbogast, a hired private investigator who leads them to the motel and the shocking truth...

Widely regarded as Hitchcock's best film, Psycho is certainly his most imitated and perhaps his most influential. Constantly twisting and turning, it opens as a romance, then turns towards a crime, ostensibly Grand Guignol, and finally switching to Freudian thriller in its last scenes. Redefining cinema, Psycho managed to spark controversy with its infamous shower scene - which remains one of the most iconic in screen history - not only for killing off its star half-way into the film and then focusing on another character for the rest, but for its shots of a flushing toilet, stabbing motions, nude body, bloodied bath, plug hole, and dead eye. Although it is only implied (no visible stabbing of flesh is shown) the murder was shot featuring 77 different camera angles, running three minutes including fifty cuts most of which are extreme close-ups; the stabbing of the flesh is audibly detailed (a knife plunging into a melon) and definitely so convincing it really doesn't need to be seen, probably why censors had so many problems with it. With Bernard Herrmann's screeching, all-string soundtrack flaring wildly, the succession of close shots combined with their short duration makes the sequence feel more subjective than it would if the images were presented alone or in a wider angle. If so pivotal to the film, what is the meaning behind that fateful shower? Subtracting the total of expenditure from the $40,000, Marion was going to come clean the next morning and accept whatever consequences lay ahead. She could no longer abide with the immorality of her well-intended actions, so stepping into the shower represents baptismal water to cleanse her sins; the spray beating down on her was purifying the corruption from her mind, purging the evil from her soul. She was like a virgin again, tranquil, at peace, smiling. We as an audience are at once alienated by Marion's death, the apparent centre of the film, and her washing away of guilt is the catalyst for her subsequent absolution, even if it is particularly terrifying and brutal. Hitchcock is effectively abandoning religion by killing off Marion prior to her repentance, Freudian psychology is the solution for the crimes of profit and passion, as always; the inexorable forces of past sins and mistakes crush hope for regeneration and resolution of destructive personal histories. Each character to enter the motel is at least once or twice reflected by glass or mirror and this alludes to both Norman's duality and good and evil altogether; everyone has two sides to their mind, and as Marion's bad deed transformed into an evil act of destruction by the hand of Norman's mind, she is absolved in the wrong way. Exiting the sweltering, unsatisfying, banal current existence in Phoenix, Marion enters the reality of crime and corruption, leading her into another world of paranoia, deceit, perversity and violence. Marion's deprivation of love, home and marriage are the elements of human happiness, wherein also lies within Psycho's secondary characters a lack of familial warmth and stability, which demonstrates the unlikelihood of domestic fantasies. The film contains ironic jokes about domesticity, such as when Sam writes a letter to Marion, agreeing to marry her, only after the audience sees her buried in the swamp. Sam and Marion's sister Lila, in investigating Marion's disappearance, develop an increasingly connubial relationship, a development that Marion is denied. Norman also suffers a similarly perverse definition of domesticity. He has an infantile and divided personality and lives in a mansion whose past occupies the present. Norman displays stuffed birds that are frozen in time and keeps childhood toys and stuffed animals in his room, where he still he sleeps in a children's bed. He is hostile toward suggestions to move from the past and remains firmly jealous of whoever enters this world he has grown to inhabit so deeply and yet comments to Marion that he only says he wants to leave; so does he or mother contradict his decisions? Light and darkness feature prominently as a result of this ambiguity, the film's dominant theme. The first shot after the intertitle is the sunny landscape of Phoenix before the camera enters a dark room where Sam and Marion appear as bright figures. Marion is almost immediately cast in darkness; she is preceded by her shadow as she re-enters the office to steal money and as she enters her bedroom. When she flees Phoenix, darkness descends on her drive. The following sunny morning is punctured by the watchful police officer with black sunglasses, and she finally arrives at the Bates Motel in near darkness. Bright lights are also the ironic equivalent of darkness in the film, blinding instead of illuminating. Examples of brightness include the opening window shades in Sam's and Marion's hotel room, vehicle headlights at night, the neon sign at the Bates Motel, the glaring white of the bathroom tiles where Marion dies, and the fruit cellar's exposed light bulb shining on the corpse of Norman's mother. Such bright lights typically characterize danger and violence in Hitchcock's films.

As effective as it is playful, Psycho is a genre piece so gripping and irrevocably gruesome it will stay ingrained in the mind longer than a dozen other similar films. It remains a true masterpiece, never to be bettered.

// Marion Crane, a platinum-blonde officeworker, is trusted by everyone who knows her as an honest, decent good woman. However, on her lunch breaks she rushes immoral activities with her lover, who is broke due to paying out alimony to an ex-wife. Desperate to marry him, Marion is handed $40,000 from a flirtatious old client. Unable to resist temptation i.e. the urge to solve her problems with her lover, she flees back to her apartment with the money. After some mental backtracking and imaginary scenarios, Marion ignores her desires and drives into the night, waking up to a suspicious policeman, whom follows her as she trades in her car to throw him off the trail. On the highway to Fairvale, Marion stops off at the empty, decrepit Bates motel; so secluded that her presence will not be noticed by the police. Upon her arrival though, she doesn't bet on the proprietor - intense, jumpy and withdrawn young man Norman - and domineering mother to make sure she truly regrets her moment of madness and want to return the money. But it is too late; she is stabbed to death in the shower by a completely shadowed figure strongly resembling invalid mother from the overlooking draconian house. Marion's lover Sam and her sister Lila become suspicious along with Arbogast, a hired private investigator who leads them to the motel and the shocking truth...

Widely regarded as Hitchcock's best film, Psycho is certainly his most imitated and perhaps his most influential. Constantly twisting and turning, it opens as a romance, then turns towards a crime, ostensibly Grand Guignol, and finally switching to Freudian thriller in its last scenes. Redefining cinema, Psycho managed to spark controversy with its infamous shower scene - which remains one of the most iconic in screen history - not only for killing off its star half-way into the film and then focusing on another character for the rest, but for its shots of a flushing toilet, stabbing motions, nude body, bloodied bath, plug hole, and dead eye. Although it is only implied (no visible stabbing of flesh is shown) the murder was shot featuring 77 different camera angles, running three minutes including fifty cuts most of which are extreme close-ups; the stabbing of the flesh is audibly detailed (a knife plunging into a melon) and definitely so convincing it really doesn't need to be seen, probably why censors had so many problems with it. With Bernard Herrmann's screeching, all-string soundtrack flaring wildly, the succession of close shots combined with their short duration makes the sequence feel more subjective than it would if the images were presented alone or in a wider angle. If so pivotal to the film, what is the meaning behind that fateful shower? Subtracting the total of expenditure from the $40,000, Marion was going to come clean the next morning and accept whatever consequences lay ahead. She could no longer abide with the immorality of her well-intended actions, so stepping into the shower represents baptismal water to cleanse her sins; the spray beating down on her was purifying the corruption from her mind, purging the evil from her soul. She was like a virgin again, tranquil, at peace, smiling. We as an audience are at once alienated by Marion's death, the apparent centre of the film, and her washing away of guilt is the catalyst for her subsequent absolution, even if it is particularly terrifying and brutal. Hitchcock is effectively abandoning religion by killing off Marion prior to her repentance, Freudian psychology is the solution for the crimes of profit and passion, as always; the inexorable forces of past sins and mistakes crush hope for regeneration and resolution of destructive personal histories. Each character to enter the motel is at least once or twice reflected by glass or mirror and this alludes to both Norman's duality and good and evil altogether; everyone has two sides to their mind, and as Marion's bad deed transformed into an evil act of destruction by the hand of Norman's mind, she is absolved in the wrong way. Exiting the sweltering, unsatisfying, banal current existence in Phoenix, Marion enters the reality of crime and corruption, leading her into another world of paranoia, deceit, perversity and violence. Marion's deprivation of love, home and marriage are the elements of human happiness, wherein also lies within Psycho's secondary characters a lack of familial warmth and stability, which demonstrates the unlikelihood of domestic fantasies. The film contains ironic jokes about domesticity, such as when Sam writes a letter to Marion, agreeing to marry her, only after the audience sees her buried in the swamp. Sam and Marion's sister Lila, in investigating Marion's disappearance, develop an increasingly connubial relationship, a development that Marion is denied. Norman also suffers a similarly perverse definition of domesticity. He has an infantile and divided personality and lives in a mansion whose past occupies the present. Norman displays stuffed birds that are frozen in time and keeps childhood toys and stuffed animals in his room, where he still he sleeps in a children's bed. He is hostile toward suggestions to move from the past and remains firmly jealous of whoever enters this world he has grown to inhabit so deeply and yet comments to Marion that he only says he wants to leave; so does he or mother contradict his decisions? Light and darkness feature prominently as a result of this ambiguity, the film's dominant theme. The first shot after the intertitle is the sunny landscape of Phoenix before the camera enters a dark room where Sam and Marion appear as bright figures. Marion is almost immediately cast in darkness; she is preceded by her shadow as she re-enters the office to steal money and as she enters her bedroom. When she flees Phoenix, darkness descends on her drive. The following sunny morning is punctured by the watchful police officer with black sunglasses, and she finally arrives at the Bates Motel in near darkness. Bright lights are also the ironic equivalent of darkness in the film, blinding instead of illuminating. Examples of brightness include the opening window shades in Sam's and Marion's hotel room, vehicle headlights at night, the neon sign at the Bates Motel, the glaring white of the bathroom tiles where Marion dies, and the fruit cellar's exposed light bulb shining on the corpse of Norman's mother. Such bright lights typically characterize danger and violence in Hitchcock's films.

As effective as it is playful, Psycho is a genre piece so gripping and irrevocably gruesome it will stay ingrained in the mind longer than a dozen other similar films. It remains a true masterpiece, never to be bettered.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Pulp Fiction review

Posted : 12 years, 5 months ago on 19 January 2013 04:05

(A review of Pulp Fiction)

Posted : 12 years, 5 months ago on 19 January 2013 04:05

(A review of Pulp Fiction)Pulp Fiction

//Arriving in the midst of formulaic Hollywood offerings, Pulp Fiction was the perfectly cultish, quirky antidote to such mind-numbing fluff dominating the cinema; refreshing, bold and striking, it spawned many imitators. Despite its heavy prevalence upon dialogue and disjointed web of events sewn together in a non-linear narrative, audiences flocked and remain enthralled by it to this very day. Peppered with great moments eaten up by actors working at the top of their game (Travolta, Willis and Thurman have never been better, and the film created the aura of greatness that currently surrounds Jackson) Pulp Fiction is primarily successful because of its witty writing, pop culture-surfing, gleeful amorality, cult tuneology and hyperkinetic energy, redefining the crime genre for the foreseeable future. Its compendium format draws upon Black Sabbath and twisty-turny crime literature, but also European movies, Amsterdam and Hollywood history. Indeed, Pulp Fiction operates in the hinterland between reality and movie reality. Into a cadre of movie archetypes — the assassin, the mob boss, the gangster's moll, the boxer who throws a fight — Tarantino injects a reality check that is as funny as it is refreshing. Whereas most crime flicks would breeze over the rendezvous between Vincent and Mia, here we actually get to go on the date— polite chit-chat, awkward silences, bad dancing — before it spirals off into a drugged-up disaster. Just as Resevoir Dogs is a heist film where you don't see the heist, Pulp Fiction never shows its main plot points or their resolution, opting instead to present the audience with detailed conversations about food and Deliverance-style rape. Moreover, after Vincent and Jules take back Marsellus' briefcase, rather than cutting to a cop on their trail, we stay with them and revel in their banal banter as they dispose of a corpse (the genius of Keitel's Wolf in this effort is a moot point — how much intelligence does it take to clean a car, then throw a rug over the back seat?)Although it is termed a crime film, its audacious story dynamics and daring array of characters would prove otherwise generally speaking, since the criminal aspect of the film is never drummed into the mind of the viewer; they're too busy being entertained. What makes the film so great is that it wouldn't work in a linearity, in criss-crossing the exposition, Tarantino forges hooks of expectation and curiosity that pay off one by one in satisfying ways with continuous scenes that interconnect a whole nexus of underworld activity. Its killer dialogue is where its cult worship began, but Pulp Fiction is an equally stimulating visual experience; from the eyeful of Jackrabbit Slims to the magical square Mia draws to underline Vincent's geekiness to Andrzej Sekula's glossy, wide angled image-crafting, the look of it is equally as imaginative without ever calling attention to itself, pop art as film. Unfathomably cool and protean, Pulp Fiction is a wondrous masterpiece of post-modern cinema.

//Arriving in the midst of formulaic Hollywood offerings, Pulp Fiction was the perfectly cultish, quirky antidote to such mind-numbing fluff dominating the cinema; refreshing, bold and striking, it spawned many imitators. Despite its heavy prevalence upon dialogue and disjointed web of events sewn together in a non-linear narrative, audiences flocked and remain enthralled by it to this very day. Peppered with great moments eaten up by actors working at the top of their game (Travolta, Willis and Thurman have never been better, and the film created the aura of greatness that currently surrounds Jackson) Pulp Fiction is primarily successful because of its witty writing, pop culture-surfing, gleeful amorality, cult tuneology and hyperkinetic energy, redefining the crime genre for the foreseeable future. Its compendium format draws upon Black Sabbath and twisty-turny crime literature, but also European movies, Amsterdam and Hollywood history. Indeed, Pulp Fiction operates in the hinterland between reality and movie reality. Into a cadre of movie archetypes — the assassin, the mob boss, the gangster's moll, the boxer who throws a fight — Tarantino injects a reality check that is as funny as it is refreshing. Whereas most crime flicks would breeze over the rendezvous between Vincent and Mia, here we actually get to go on the date— polite chit-chat, awkward silences, bad dancing — before it spirals off into a drugged-up disaster. Just as Resevoir Dogs is a heist film where you don't see the heist, Pulp Fiction never shows its main plot points or their resolution, opting instead to present the audience with detailed conversations about food and Deliverance-style rape. Moreover, after Vincent and Jules take back Marsellus' briefcase, rather than cutting to a cop on their trail, we stay with them and revel in their banal banter as they dispose of a corpse (the genius of Keitel's Wolf in this effort is a moot point — how much intelligence does it take to clean a car, then throw a rug over the back seat?)Although it is termed a crime film, its audacious story dynamics and daring array of characters would prove otherwise generally speaking, since the criminal aspect of the film is never drummed into the mind of the viewer; they're too busy being entertained. What makes the film so great is that it wouldn't work in a linearity, in criss-crossing the exposition, Tarantino forges hooks of expectation and curiosity that pay off one by one in satisfying ways with continuous scenes that interconnect a whole nexus of underworld activity. Its killer dialogue is where its cult worship began, but Pulp Fiction is an equally stimulating visual experience; from the eyeful of Jackrabbit Slims to the magical square Mia draws to underline Vincent's geekiness to Andrzej Sekula's glossy, wide angled image-crafting, the look of it is equally as imaginative without ever calling attention to itself, pop art as film. Unfathomably cool and protean, Pulp Fiction is a wondrous masterpiece of post-modern cinema.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Scarface review

Posted : 12 years, 5 months ago on 10 January 2013 03:19

(A review of Scarface)

Posted : 12 years, 5 months ago on 10 January 2013 03:19

(A review of Scarface)Decadent, exuberant and outlandishly big, Brian DePalma's operatic grandstand slyly and ironically envisions America's still-thriving meritocracy with baroque verve. Neon-emblazoned, hyperkinetic 1980s Miami is sensational to look at, thanks to the visceral extravagance and gloriously fervid visuals; sleazy, electronic, over-styled and dreamily captured in wide-angled framing, it is beautiful, subversive and worthy of its title as a pop culture touchstone.

Either in discos, country homes or geometric, personally made mansions, every frame pops with its obscene array of multi-coloured magnetism; cleverly realistic blood is spilled and splattered via countless bullet wounds (also by way of a buzz-chainsaw, an infamous scene at the time) throughout, but especially at the film's conclusion, whereby a literal bloodbath takes place in Tony's mansion and ends in a blue pool below the iconic neon pink 'The World Is Yours' globe statue, perhaps the most symbolic image of excess in all of cinema.

Right from outset, DePalma transposes the action of Miami from the refugee boats exiting Cuba, many of which are criminals expelled from their homeland by Fidel Castro in an attempt to empty the overcrowded jails. Tony is ferociously determined to take advantage of his new lavish, murkily and hierarchically-structured criminal surroundings, viewing it as his world to own; the crux of capitalism and strives to achieve the American dream. Several months dwelling in a refugee camp, Tony parlays a successful hit on a former Cuban government official into a connection with a drug lord; from there, he rises to the top, but crashes headlong into a spiral of excess and paranoia.

His relationships with Manny and Elvira, his trophy wife, are integral to the unhinged state of mind he descends into, both distrusting and persecutory; Elvira is a lonely junkie who cannot have children and Tony only truly loves his sister, Gina, whom he inexorably introduces into his world, tainting her purity and vapid innocence which he personified her as, exploding with jealousy whenever men covet her, especially Manny, a womaniser with good intentions.

Scarface, beyond its style, possesses a tragic heart buried in its many layers and contradictions, exemplified by Tony refusing to murder his associate's national exposer and his young family: eschewing the theory of his amorality, and crafting a semi-human gangster. Ultimately, Scarface dooms Tony once he reveals his humanity, and how it builds towards his demise is one of the most machismo, frenetic arcs of total self-destruction of a character, captured with lightning pace by DePalma. Tony expresses regret for his deplorable actions, but that is the fatal fault in his personality: his fierce protectiveness of Gina overspills into irrational rage; his power is slowly gained - he murders his boss and overtakes his life, staring out of the window of his condo - but is quickly drained. And as with any gangster movie, the dominant mood is what goes up must come down - success and power do not mix: when the protagonist can no longer find anything to overrule, objectify or possess, he loses everything and drastically falls apart, because nothing is ever enough, it's a film that is bleak and futile, particularly in its exploration of addiction, after all, that's what it is really about, it was written with that intention by Oliver Stone. Its the evolution, fatal flaws and complexities of his fragmented soul that make Tony Montana so influential, and Al Pacino's cataclysmic, bravura performance is mesmerising and once seen, impossible to forget.

Scarface remains an eminently quotable, compulsively watchable template for modern-criminal deconstructions of the American Dream, a cultural totem that effectively became the genesis of hip-hop iconography, with florid pleasures that can never be exhausted; it is a garish piece of pop art that walks a thin white line between moral drama and hip-hip classic.

Either in discos, country homes or geometric, personally made mansions, every frame pops with its obscene array of multi-coloured magnetism; cleverly realistic blood is spilled and splattered via countless bullet wounds (also by way of a buzz-chainsaw, an infamous scene at the time) throughout, but especially at the film's conclusion, whereby a literal bloodbath takes place in Tony's mansion and ends in a blue pool below the iconic neon pink 'The World Is Yours' globe statue, perhaps the most symbolic image of excess in all of cinema.

Right from outset, DePalma transposes the action of Miami from the refugee boats exiting Cuba, many of which are criminals expelled from their homeland by Fidel Castro in an attempt to empty the overcrowded jails. Tony is ferociously determined to take advantage of his new lavish, murkily and hierarchically-structured criminal surroundings, viewing it as his world to own; the crux of capitalism and strives to achieve the American dream. Several months dwelling in a refugee camp, Tony parlays a successful hit on a former Cuban government official into a connection with a drug lord; from there, he rises to the top, but crashes headlong into a spiral of excess and paranoia.

His relationships with Manny and Elvira, his trophy wife, are integral to the unhinged state of mind he descends into, both distrusting and persecutory; Elvira is a lonely junkie who cannot have children and Tony only truly loves his sister, Gina, whom he inexorably introduces into his world, tainting her purity and vapid innocence which he personified her as, exploding with jealousy whenever men covet her, especially Manny, a womaniser with good intentions.

Scarface, beyond its style, possesses a tragic heart buried in its many layers and contradictions, exemplified by Tony refusing to murder his associate's national exposer and his young family: eschewing the theory of his amorality, and crafting a semi-human gangster. Ultimately, Scarface dooms Tony once he reveals his humanity, and how it builds towards his demise is one of the most machismo, frenetic arcs of total self-destruction of a character, captured with lightning pace by DePalma. Tony expresses regret for his deplorable actions, but that is the fatal fault in his personality: his fierce protectiveness of Gina overspills into irrational rage; his power is slowly gained - he murders his boss and overtakes his life, staring out of the window of his condo - but is quickly drained. And as with any gangster movie, the dominant mood is what goes up must come down - success and power do not mix: when the protagonist can no longer find anything to overrule, objectify or possess, he loses everything and drastically falls apart, because nothing is ever enough, it's a film that is bleak and futile, particularly in its exploration of addiction, after all, that's what it is really about, it was written with that intention by Oliver Stone. Its the evolution, fatal flaws and complexities of his fragmented soul that make Tony Montana so influential, and Al Pacino's cataclysmic, bravura performance is mesmerising and once seen, impossible to forget.

Scarface remains an eminently quotable, compulsively watchable template for modern-criminal deconstructions of the American Dream, a cultural totem that effectively became the genesis of hip-hop iconography, with florid pleasures that can never be exhausted; it is a garish piece of pop art that walks a thin white line between moral drama and hip-hip classic.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

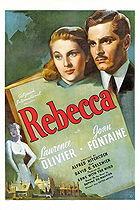

Rebecca review

Posted : 12 years, 6 months ago on 27 December 2012 03:24

(A review of Rebecca)

Posted : 12 years, 6 months ago on 27 December 2012 03:24

(A review of Rebecca)Rebecca

// David O. Selznick's influence ruined the possible greatness of Hitchcock's first American production, just as he later did with Spellbound. During the Manderley segment of the first portion, the film was an interesting psychological thriller involving a spectre of the past haunting memories. Swerving between theories and capturing obsession most brilliantly, Rebecca is special in those moments you really want it to be, but the last portion somewhat dampens the suspense of those opportunities of greatness by abandoning the ominous shadows and evolving characters. Mrs de Winter II spends most of her time as a new bride slowly being persuaded by the creepy housekeeper, Mrs Danvers, that her mysterious, somewhat unreachable husband Maxim is still hopelessly in love with his dead wife, not to mention her insistence that Manderley remains as it did in the past. Once Maxim reveals that he killed his beautiful, enchanting and unfaithful wife, the film turns sour, attempting to be suspenseful as the truth is threatened to be outed by Rebecca's lover and cousin only to be revoked at the last minute when it turns out Rebecca was dying anyway and so had the motive to have drowned herself in the boat.

Despite its obvious faults, the scenes between Mrs Danvers and Mrs de Winter II are the most memorable: typically Hitchcockian psycho-sexual subtext with gothic ardour. It never reaches the heights of exploring obsession as in Rear Window, Vertigo or Psycho, but this is one of Hitchcock's tentative, first attempts at the subject and it's very decent, but no masterpiece.